Collected Stories of the Grand River

TABLE OF CONTENTS

POEM – ARTEMESIA SPRING

AUTHOR – JOHN BUTLER, 1999

Here in the sly waters

of the swamp

Here in the busy waters

of the creek

Here in the siren waters

of the lake

Here in the languid waters

of the mist

Here in the brooding waters

of the rain

Nomadic colonies

of hope

Set sail.

STORY – ONE STREAM, TWO DREAMS

Author: John Butler

Twice in the last hundred years, a little spring-filled farm valley in Proton Township has hosted the dreams of people to create a gathering place for their communities – the community of rural and small-town folks needing a place to forget, for a day, the tough times of the dismal 1930s, and Ontario’s community of competitive water skiers from the 1970s to the present day.

In 1930, Proton farmer Wilfrid Black, his wife Minetta and their teenage son Robert (Bob) began the hard work of creating a recreational facility for local people on their stone-strewn farm. Wilfrid and his son dammed a spring-fed creek flowing through the farm’s valley. They dug a lake bed using a horse-drawn slush scraper (like a large flat-bottomed sugar scoop) to skim off thousands of scraper-loads of earth. They dumped the dirt in the northeast quadrant of the lake bed, building up the core of a stone-faced dam to create their fourteen acre lake. They then hauled in two hundred wagon-loads of stone to finish the dam. In winter the Blacks carted sand from a hill on the farm and spread it on their frozen lake. When the ice melted in spring they had a lake with a sandy beach, a stretch of grassy meadow and a dance floor, ready for paying customers – a place thereafter known as Black’s Beach.

The daughter and the two sons of Bob Black and his wife Dell (Diane, John and Don) remember the driving force behind their father’s and grandparents’ labor. One motivation, common to farmers during the Great Depression, was the need to make money any honourable way they could. But Black family members were sociable people, constantly welcoming neighbours into their home. John Black recalls the Farm Forum evening meetings hosted by his parents for the neighbours, mixing socialization and good food with learning via the Forum’s radio broadcasts. The family operated Black’s Beach as an extension of their hospitality – as a community service. Family members say the Blacks made a few dollars from it but they didn’t get rich.

The Beach catered to three “crowds”. First, it served local people who needed a low-cost place for swimming and picnics on summer days. A dollar would admit a whole family, and boat races and ball games enlivened the day. Black family members recall that on special days such as July 12 (a day for Orange Lodges to congregate and celebrate) and on July 1, crowds at the Beach numbered in the hundreds.

On Saturday evenings, a different crowd used the facility – young people needing a place to dance and mingle. At first the Beach merely provided a roped-off open-air dance floor (a quarter let you through the rope and entitled you to three dances), but that was soon replaced by a frame dance pavilion.

Jean Hutchinson, who remembers visiting Black’s Beach as a child, points out that music was part of farm life. Fiddle players augmented by banjos, guitars and accordions were common, and it was these local musicians who formed the bands that performed jigs, reels and waltzes at the pavilion. Hutchinson recalls that one of her relatives was a square dance ”caller” at the Beach pavilion at a time when just about everyone knew how to square dance. As a nod to the community’s Scottish roots, the Haw Pipe Band often performed at Black’s Beach.

Hutchinson recalls that dances at the beach were lively affairs, with dancers’ yells of enthusiasm adding to the music. Although the Blacks didn’t sell alcohol (Prohibition was in force in Ontario), booze probably made its way to the dances, stashed in coat pockets. The popularity of the raucous dances and lively picnics, coupled with evening alcohol, may have prompted the newspaper correspondent from the nearby village of Swinton Park to write disapprovingly in her July 1936 column in the Durham Chronicle:

“Black’s Beach has been widely patronized during the warm days and nights, also on Sundays. Many are, we fear, spending their substance on riotous living, and their money for that which is not bread, coming for miles, not always very orderly, for a dip in the cold spring water.”

Providing a gathering place was only one of the services the Blacks offered. Their family-operated snack bar sold hot dogs (a dime each), pop, coffee and home-made ice cream. Thanks to laborious hand cranking by family members and helpful neighbours, the family’s ice cream maker produced 2.5 gallons at a time in the Blacks’ farmhouse kitchen: picnic-goers consumed up to 15 gallons a day. In making this confection, the family used ice they had cut from the lake in winter and stored under sawdust in sheds on the farm until it was needed in the summer.

The third crowd comprised local skaters and hockey players who enjoyed the rink and the skaters’ change-hut the Black family built and maintained each winter on the sheltered west side of the lake. The rink became home ice for to the Swinton Park Black Hawks comprising two Blacks, two Goheens, two Haws and a few other locals. Ever inventive, three women from the Black family sold hot dogs and cocoa to the freezing hockey crowd. Since rural electrification wasn’t widespread at the time. Wilfrid Black bought a generator to provide light for the skating rink in winter and for the dance pavilion in summer.

By the end of the 1930s, Black’s Beach had run its course. Young men had gone off to war, depleting the dance crowds, and Wilfrid’s son Bob took a construction job in Gananoque and then in Sudbury, Hamilton and on the Alaska Highway, depleting the family workforce in Proton. Black’s Beach closed, and the Blacks sold the buildings on the site for removal to Irish Lake north of Flesherton.

In 1973, waterskiing enthusiast Alan Ashton bought the lake and the strip of property surrounding it. The lake was renamed Ashton Lake, the name it holds today. This body of water is the ideal length, width and depth for competitive waterskiing. Ashton turned the property into a waterskiing facility, but honoured its Black’s Beach heritage by inscribing its history on a larger boulder on the site.

Ashton’s friend Cardy Wells bought the property from Ashton in 1974, built his summer house there, and bought the surrounding 160 acres in 1989. Wells, now in his 70’s, developed a passion for waterskiing at the age of eight (a passion the boy’s family considered slightly potty), and he still skis every day he can (including Florida winter waterskiing). Wells’ daughter, a dentist living in Sudbury, inherited her father’s passion for the sport.

A Canadian waterskiing champion and slalom record-holder, Wells still owns the property and he has turned the lake – now entirely spring-fed – into one of the three top competitive waterskiing lakes in Ontario. Wells hosts a waterskiing club at the lake and a number of championship events have been held there. He expects it will be the site of a national championship in the near future. An infectious advocate for his sport, Wells welcomes inquiries about the club or about competitive waterskiing in general – call him at 1-519-275-0706. Says Wells, “Creating this facility has been the fulfilment of a dream of mine. We’ve done enough maintenance and preservation work on our site that it can still be used for waterskiing 200 years from now.”

Lakes don’t speak to those who visit them. But if Black’s Beach / Ashton Lake could speak, it would likely speak of the dreams of two families – the Black family and the Wells family – and it would speak of how its clear cold waters nourished both those dreams.

THE MIGHTY GRAND – TRISTAN VOGEL

“The mighty Grand was looking like a snake cutting through the landscape towards the horizon”

Tristin Vogel

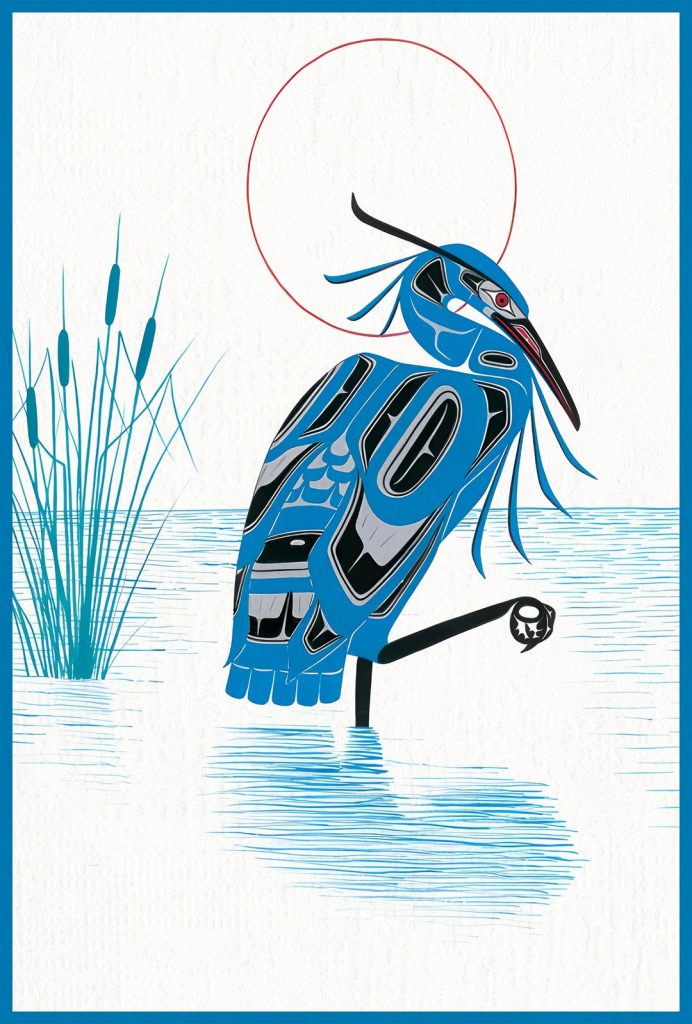

STORY – THE ONE WHO SPEAKS WITH STONES

The One Who Speaks with Stones. They say the Blue Heron was not born from egg or sky—but carved from river rock by the first hands of the land. He rose when the world needed a listener, not a voice.

By the water’s edge, he speaks with stones—the old ones who remember when the forest was still a whisper. He learns their quiet language, waits through seasons, never rushing answers. The wind forgets, but the stones do not. And so, neither does he.

The elders say he appears when a heart is heavy and silence is needed more than sound. He does not offer comfort. He offers truth—the kind that arrives slow, like dawn through fog.

He walks the shoreline between worlds: land and water, memory and becoming.

He is not a messenger. He is the pause before the message.

And in that stillness, healing begins.

We call him T’łikwaan — He Who Listens to What Is Buried.

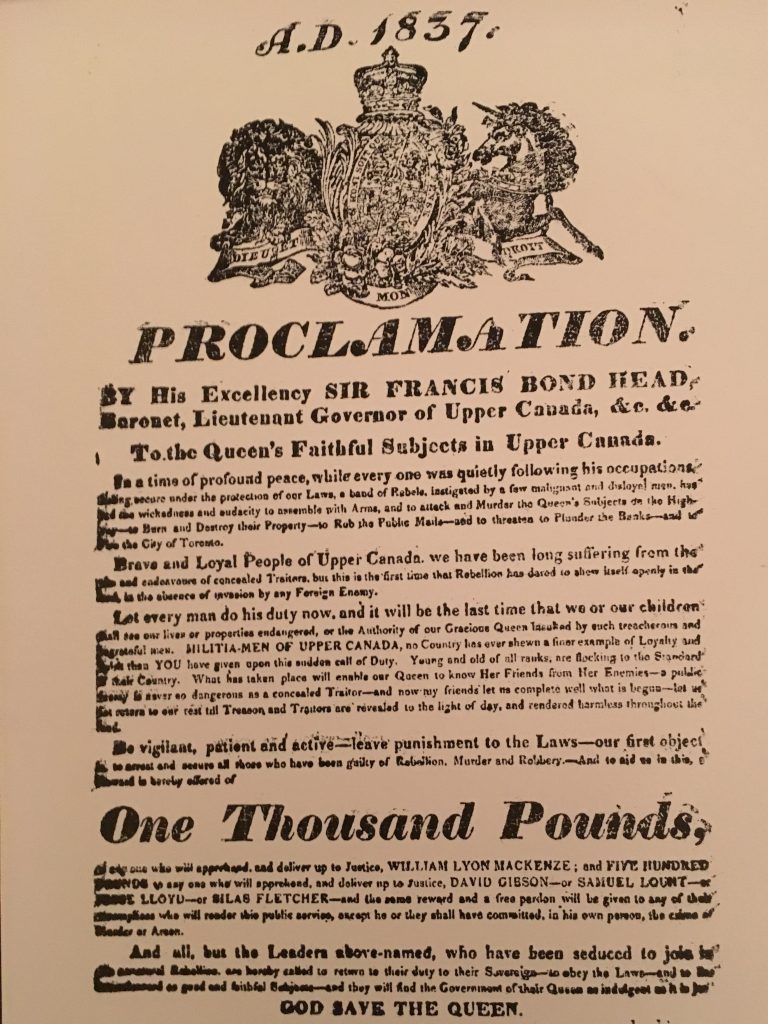

THE PROCLAMATION

Willam Lyon MacKenzie right after the 1837 Farmers Revolt fled for his life from Toronto and stayed over one night at the Sharp Farm in Glen Morris. If you want to hear the full story come to Glen Morris and hear local artist/singer Karen Murray-Hopf play James Sharp right by the Grand River… a bagpiper makes an appearance too…

See more of the story below.

STORY – JAMES SHARP’S DIALOGUE FROM VOTR

On that very cold December 8th – William Lyon MacKenzie came charging across the Glen Morris bridge and I met him, brought him under the cloak of darkness back to our farm. Mary gave him stew, and I grog from my bottle. He was wild-eyed, and near frozen to death. He muttered thank you as he ate and drank and the only thing that stopped him from doing either was a sound, real or imagined, coming from outside the door. I eventually got up and stood on lookout while he ate. He began to relax after the meal and he talked to us about the importance of democracy, about holding free and fair elections, and about equality. The more he talked, the more I listened. What he had to say I’d heard my father say, was akin to some of the thoughts Mary and I had shared. Mary offered him a blanket, and he dozed by the fire. It was an uneasy sleep as he needed to be on his way – the militia wouldn’t be far behind. But he’d ridden over 65 miles, in 7 or 8 hours, and both he, and more importantly his horse, needed to rest. I sat beside him until he jumped awake an hour later. Must be gone, he shouted. Mary had food ready in a travel bag. I got his horse from the stable. “To die fighting for freedom is truly glorious,” he said, as he mounted the steed and as I pointed him in the direction for the United States – and then he was gone.

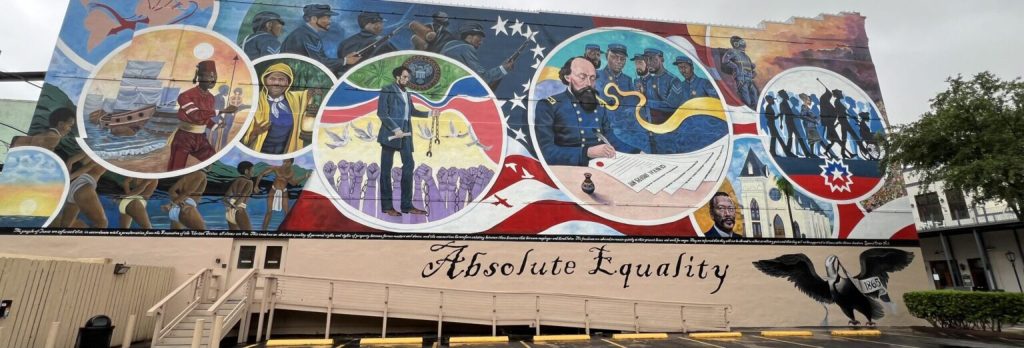

AT THE CONFLUENCE OF THE WALK TO FREEDOM AND THE WATER WALKERS

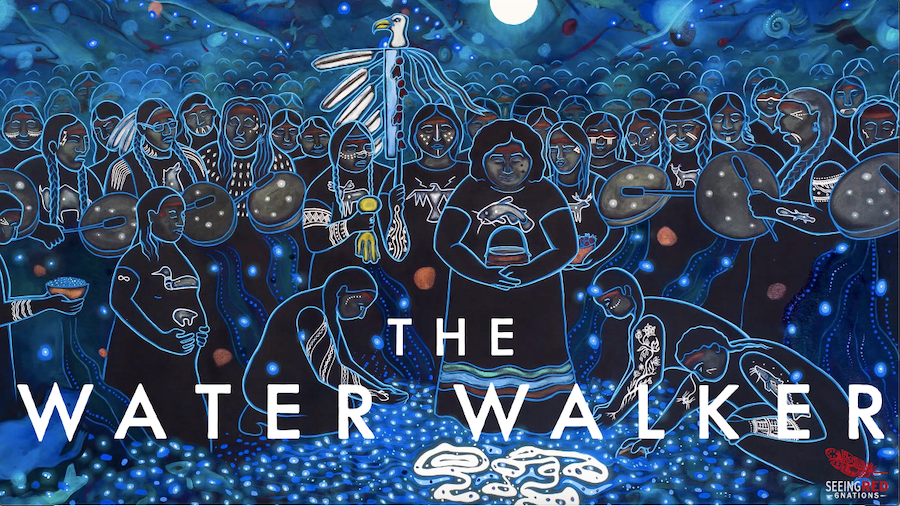

Over the course of creating THE VOICE OF THE RIVER we’ve met many people, enjoyed many grand experiences, in so many different communities. We met the Water Walkers in 2022 when they created a Water Ceremony on Laurel Creek prior to our second Prologue in the Abe Erb Grist Mill in Waterloo. It was a cold day, the sun was shining, and some of the water in the Creek had turned to ice. The Water Walkers walk to honour Nibi (water), they speak, sing and pray to her spirit, and offer petitions for healthy rivers, lakes and oceans for future generations. We are honouring them and the water at dawn on July 27th (6am) at Bissel Park – as a part of the Voice of the River Tour – all are welcome.

Not long ago we connected with Ken Johnston who is walking from New York State to Owen Sound to honour the Underground Railroad and those who sought freedom from persecution. He will be walking in the Grand River Watershed and we are connecting with him where the Speed and Eromosa Rivers meet at Guelph. Finding community in the moment, letting the River guide us, and discovering the current and following the flow, is the way this project continues to unfold. And in that – is learning, hope, love, and respect. Join us at the confluence as we tour down the River this summer.

Peter Smith

THE IROQUOIS CREATION STORY: MYTH OF THE EARTH GRASPER

We’ve been introduced to so many grand stories from along the River and across her Watershed in the last three years and there is one that came from a book edited by John Mohawk called: The Iroquois Creation Story: Myth of the Earth Grasper. It was written in 1899 – by 100 year old Chief John Arthur Gibson and ennologist J.N.B. Hewitt. That summer, the two men gathered in a cabin on the Grand River and worked by daylight and oil lamps at night to type out the Creation Story as recounted by Chief Gibson. He was believed to be one of the last speakers of the Creation Story in its entirety in the oral tradition of the Haudenousanee. The fear that Hewitt had was the Story would be lost if it wasn’t typed out to be preserved for future generations. The Chief agreed to recite in Seneca and Hewitt, a Seneca speaker, typed it into English. While the 10,000 year old Creation Story was being committed to paper in that cabin on the Grand River, a few miles up River, at almost the same time – Alexander Graham Bell was inventing the telephone with the first words spoken by his father in a crude one way device between Tutela Heights and Paris, Ontario. And what Bell’s father said to his son was this: To be or not to be…

We haven’t presented this story to an audience – though it’s been something we’ve wanted to – until last Saturday night in Guelph. Young Cayuga actor, Austin Silversmith, stood in front of the audience on a beautiful August evening and told them this story… As he spoke it at the confluence of the Speed and Eramosa Rivers that flow into the Grand, the story came alive once again. And as we continue to work on it , shape it, it is now a part of the Voice of the River and will be heard in presentations as we make our way down the River to Lake Erie, and at the Grand Finale at Chiefswood Park at Six Nations on August 23rd… Amazing the stories this River holds

Peter Smith